The Alliance is the newest member of The Inland Seas Education Association fleet of schooners. It was purchased to provide more opportunity for schools and families to learn about the Great Lakes. It will take a journey of about 3,000 miles to sail it from Maryland, to its new home in Suttons Bay, Michigan.

On Thursday, June 29, 2023, I’m up at 4:00 am to pack the truck and pick up Rob on the peninsula before heading up to Suttons Bay to meet the rest of the crew at The Thomas M Kelly Biological Station. We will be driving to Montreal, Canada to meet the new Inland Seas Schooner the Alliance. Traveling with me are fellow crew members Earnie, Wayne, Rob and Rachel.

We will be joining Captain Ben, Pete, Karsten, Tom, and Kari for the third leg of the transit of the Alliance that began back in Maryland on the banks of the Chesapeake River. The first leg left on June 17 Traveling from Maryland to Lunenburg. The second leg sailed from Lunenberg to Montreal where we will relieve the crew and continue on the third leg of the journey.

This has been another summer of smoke from wildfires burning up in Canada. Some days when the wind is from the North, it is as thick as fog, and it seems to get thicker now, as we drive South and East into Canada. About 70 Kilometers from Toronto a sign says we are entering the Niagra Escarpment. I can see a change in the geography of the region and know that just south of where we are is the Niagara Falls, just one of the many obstacles we will have to circumvent on our sail back.

It seems like it takes us forever to get through Toronto while we snack on peanuts, M&M’s and Cashews, thanks to Rachel for providing them for us. We finally arrive at the Port of Montreal after dark about 10:00 PM, and we can see the Alliance through the gate, tied up to the Break wall.

We were given a number to call when we arrive, so the port authority can remotely open the gate for us. Rob calls the number and a man answers speaking French and before he can explain what we needed he hangs up? We try again and Rob try’s speaking broken French and he hangs up again? This time Rachel calls and a woman answers who speaks English and immediately opens the gate for us.

We drive through the gate and park next to the Alliance where the crew we are replacing are moving their gear onto the break wall. We start unloading our gear and after a short welcome we go below and select a cabin and bunk. Rob and I are assigned Cabin one, port side, forward and I take the lower bunk. We unpack and settle in for the night.

We are awakened at about five am by an ocean freighter pulling into the port and using its bow thrusters to dock at the pier next to ours. The name on boat is the CT MA Voyager II that travels between Montreal and Newfoundland. I watch from our deck as they begin to unload their cargo. After this I go to the galley for French toast and sausages prepared by Jeanie, our fabulous cook.

After breakfast we have an inspection by the St. Lawrence Seaway Authority to make sure we are properly equipped to continue through the St. Lawrence Seaway Locks. We also take on a thousand liters of diesel fuel for the trip. The captain plans to leave early tomorrow morning. I help carry off some trash left over from the week before.

After sandwiches for lunch, we have the rest of the afternoon to explore Montreal, so around Montreal old town, we did roam. Since this was Canada Day weekend there was a carnival atmosphere with a lot of tourists and celebrations in the streets. We stopped at a museum of illusions and as we roamed through old Montreal, we came upon a statue in the city square. I figured this must be a statue of some famous French explorer but Since everything was in French, I couldn’t tell who it was.

It was a hot day so We stopped at an ice cream shop to refresh ourselves. We walked through a carnival and had dinner in an old building that served its signature dish of Poutine and chicken which is actually just French-fries and gravy “eh”. We took a short cut back to the boat crossing over the old locks that used to bypass the rapids and stoped in at a blacksmith shop for a short tour.

It was Jacques Cartier, a French Explorer, who discovered the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1534. The following year, he sailed up river and found an island and a wild rapids blocking any further travel up river. This is probably why the upper Great Lakes were explored before the lower Great Lakes. He named the island Montreal.

Paul de Chomedey, Sieur de Maisoneuve, traveled to the island from France in 1642 with a group of colonists to colonize Montreal and became the islands first governor. It soon became a hub for the fur trade and exploration of the northern Great Lakes. Further travel north and west however, would have been from the Ottawa River and eventually connecting in Georgian Bay on Lake Huron. The statue, I find out later is for Chomedey.

Saturday, July 1

I am up a 6:00 am for breakfast at 7:00. We will be leaving this morning after our travel planning meeting with Captain Ben. Because we are a large craft, we will not have to tie up in the locks but can remain in the center while the locks lift us to the next level. We all review the duty roster with the captain, and I find I am on the 4:00 to 8:00 am and the 4:00 to 8:00 pm shifts. Sun rises and sunsets. What could be better than that. With me on this shift includes Kari, and Pete the assistant Captain. We will also have some galley duties which include cleaning the galley surfaces. Kari, one of our mates, brings a fresh set of “Alliance” pennants for the crew to sign. They will be flown above the boat on our leg of the trip.

Meals will be at 8:00, 11:30 am, and 3:45 pm. We will use jacklines at night except when we are in the locks where it will be “all hands on deck”. After the meeting we make the boat presentable for the trip. The captain reviews the charts and all the check points along the way for the 7 locks we will have to navigate between here and Lake Ontario.

As we were waiting for the call from the lock master, we did a couple of drills. First a man overboard drill and then a fire drill while still secured to the pier. Finally, around 3:30 pm, we get the clearance to begin our journey up the St. Lawrence. We Cast off the lines, coil them, and move away from the pier.

As we approach the entrance to the St. Lawrence River, I can’t help but notice how turbulent the water is flowing by the harbor entrance. But, this isn’t just any water flowing by here. It is the water from all five of our great lakes. It is a virtual “alphabet soup”, representing thousands of micro habitats that make up the great lakes and connecting waters, all racing to the Atlantic to tell their stories to the sea.

The captain pushes the bow out into the turbulent river and turns downstream, the only direction we can go because of the Lachine rapids just up stream. We travel down and across the current behind St. Helen’s Island to the entrance of the St. Lawrence Seaway and the calm waters of the canal. The St. Lawrence Seaway opened in 1959 and for the first time, ships from around the world could now enter our Great Lakes and sail as far inland as Duluth Minnesota.

Not very far ahead is the St Lamberts Lock. Our first lock and it is all hands on deck. This lock, and all the rest on the St. Lawrence, is 14 meters high. That’s about 45 feet high and over twice the height of the locks at Sault Ste Marie. It was a little stressful trying to keep the boat in the center of the lock.

The water came into the lock from below the boat and the turbulence moved us towards one wall and then the opposite wall. We had to keep moving the bumpers from one side of the boat to the other while the captain, skillfully using forward and reverse engines, tried to keep us centered in the lock.

Rob uses a long pole to push against the lock wall to keep the bow sprit from making contact. In retrospect, I think it may have been easier just to tie up to one side of the lock, but we made it through without any part of the boat touching the wall and now more prepared for the next lock.

An interesting fact, the locks on the St Lawrence Seaway are only 766 Feet long and 80 Feet wide. Sault Ste Marie Michigan has a 1,000 foot lock and they are in the process of building a second one the same length. These locks are for the big lake boats and not the Ocean freighters.

The canal and lock system parallels the river here and the Cote Ste Cath Lock is not too far ahead. The banks of the canal are covered in vegetation and trees except next to the locks where it’s concrete with places to tie up. It looks like we are just motoring up a lazy river.

It’s raining now and continues to rain the rest of the night. We make it through the second lock, the Cote Ste Cath Lock, much easier this time and continue on as the canal connects us back to the river. The river widens out into Lake Saint-Louis here and we now follow the red and green bouys to stay in the shipping channel across the center of the lake.

At the end of this lake we come to the Beauharnois locks. There are two locks close together here that take us over the Beauharnois power dam and into the Beauharnois Canal. This canal takes us around the Pointe-des-cades Rapids. When we arrive, however, the lock has an electrical problem with a boat in the lock so we have to tie up for awhile and now it’s getting dark.

It was well after dark by the time the lock was fixed and the freighter moved out and downstream. We moved into the lock and passed through this lock and the next lock without too much difficulty as it continued raining through the night.

Sunday morning, we went through two more locks on the American side of the river that were separated by the Wiley Dondero Canal. We were then brought back out into the river. Later we were passed from behind by an ocean freighter from Algoma Central.

The next and final lock on the St. Lawrence Seaway, is the Iroquois lock which is much lower than the other locks on the seaway. This lock takes us around the Iroquois control dam that is essential in controlling the water levels in the river. It’s height depends on the height of the river which changes with spring rains and summer droughts that change the flow. Today, it appears to be the same height on both sides of the lock so they open the doors and we pass through without stopping.

We are now back out into the river and spend the rest of the day watching the scenery as we follow the buoys to stay in the shipping channel. I am surprised that we only meet a few ocean freighters as we motor up stream. The traffic seems very light.

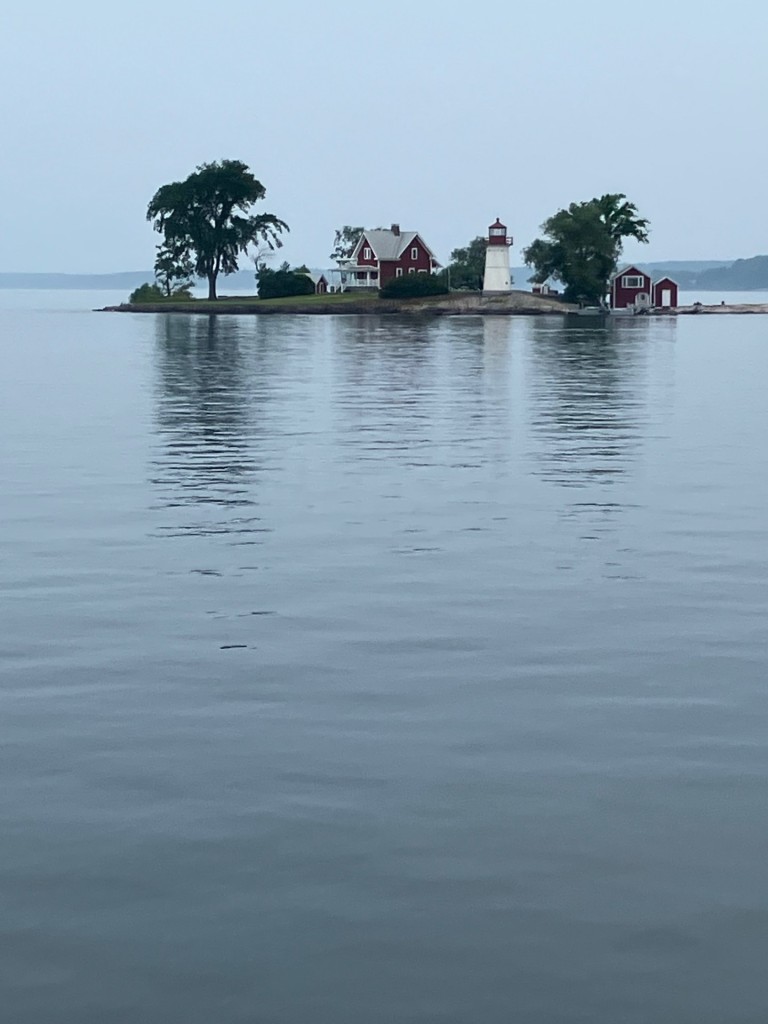

We travel through a picturesque part of the river lined with beautiful homes and After dinner we enter the Thousand Islands area of the river. Here, the river widens and is filled with islands of all sizes. Some as small as huge rocks, others just big enough for a house and boat dock and still others with many homes and small harbors. There are even a few islands with castles. We all stand on deck and watch this panorama go by as the sun goes down.

Monday morning, as I awake at 3:30 am for my 4:00 am watch, I notice a difference in the sound of the engine. It is now running at full speed and there is also a change in the air. It is a little cooler and fresher and this could mean we are out of the St. Lawrence River and are now on Lake Ontario.

As I leave my forward cabin to climb the ladder and emerge on deck, my feelings are confirmed. We entered into Lake Ontario sometime in the middle of the night. Pete said there was some turbulence at the entry to the lake. It’s as if the river did not want to give us up and was trying to hold us back.

Today as I take the helm, I am now steering by a glowing compass in the dark with a heading of 250 degrees West Southwest. We no longer have any landmarks or buoys to steer by, only open water in all directions. It will take us most of the day to reach the Welland Canal at the other end of Lake Ontario.

Lake Ontario is the Eastern most Great Lake and the smallest in surface area of 7,340 square miles. However it exceeds Lake Erie in volume because of its great depth of 802 feet. Interestingly, early geographers considered all of the Great Lakes to be part of the St Lawrence River. They decided that the river actually started up in Minnesota with the St Louis River that flows into Lake Superior. That water then spills from Great Lake to Great Lake until it flows out of Lake Ontario and into the St. Lawrence. Of course this was a great simplification.

Lake Ontario is different from the other 4 Great Lakes in that it has always been connected to the Atlantic Ocean. Since the ice retreated from the last ice age about 10,000 years ago, Lake Ontario has been home to many anadromous fish species, both desirable and undesirable. Species like Atlantic Salmon and Lake Trout, and species such as the Sea Lamprey and Alewives. The upper 4 Great Lakes were isolated from Lake Ontario and the Atlantic by the Niagara Escarpment until this was breached by the Welland Canal in 1829, allowing the Sea Lampreys and Alewives, that were already accustomed to living in fresh water, entrance to the rest of the Great Lakes.

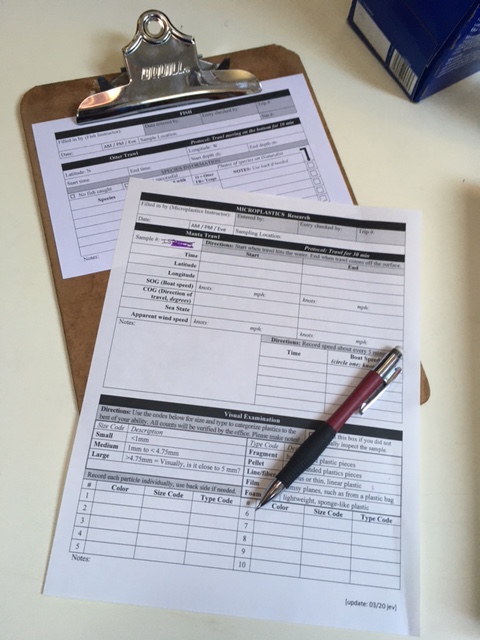

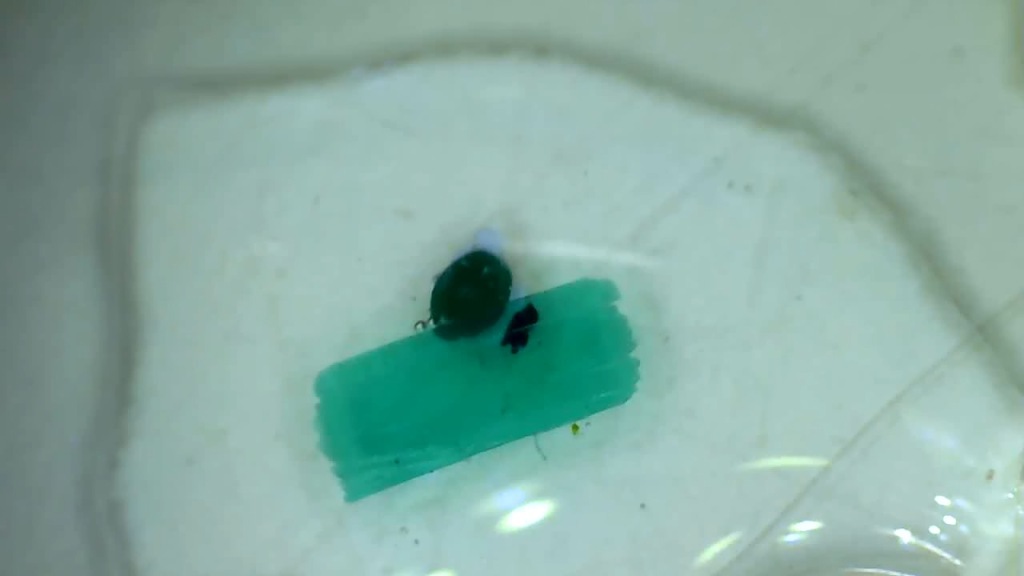

There is not much to see except water when your out in the middle of such a large lake. You have no site of land or any landmarks. So having a freighter pass us from behind becomes an event. On bow watch, I see what looks like a marker bouy in the distance which is not on the charts. As we came closer, we discovered it was just a big red Mylar balloon. We try to catch it but missed. Unfortunately, more micro plastics in the lake.

Traveling on the big lake gives me time to become familiar with the Alliance. The boat is much larger than the Inland Seas and has more deck space. The deck is on two levels with about a foot drop down from the stern to midships. Something I had to get used to in the dark. It also has two fire hoses with a pump that is run off a Generator.

Since the Alliance has three masts, there are more pin rails on the outside and on the inside of the deck and I spend some time examining the lines to learn what each line is for. I also learned that the first mast is not the main mast but is the Mizenmast. The Mainmast is in the middle followed by the Foremast.

The Welland Canal in Ontario,Canada, consists of 8 locks and traverses the Niagara Escarpment between Port Waller on Lake Ontario, and Port Colborne on Lake Erie. The total length is 27 miles and will raise our boat about 167 feet to bypass Niagara Falls. These locks, like the ones on the St. Lawrence Seaway, are also very high – 14 meters which is around 45 feet.

We enter the first lock on the Welland Canal with experience now and the lock crew drops us lines to keep our starboard side against the wall of the lock. The rest of the locks will line up in good order and we should be through them in a few hours.

After the second lock, my shift ends and I am relieved of duty since we no longer need all hands on deck. I figure by the time my shift begins tomorrow, we should be cruising across Lake Erie. Back in my bunk I hear us go through one more lock and I fall asleep.

When I awake Tuesday morning at 3:30 for my first shift I am surprised that I don’t hear a sound. I hear nothing from the engine room and nothing from the crew. Just silence. I also can’t feel any motion and wonder what has happened. I quickly dress and climb the ladder to topside, and emerge on deck to find no crew on duty.

I look around and can’t see anything past the bow of the boat and discover we are tied up to shore just below one of the locks. The fog is so thick they must have closed the locks sometime during the night. I walk to the starboard side and see a sign that says we are tied up somewhere on the canal below lock 8, the last lock on the canal.

I ascend the steps into the galley and make coffee. A little while later Rob comes in with the same questioning look, so we sit and talk over coffee. Evidently, according to the captain, the fog started rolling in during the transit of the locks last night and after the seventh lock the lock master shut everything down until visibility improves.

Finally, around 10:00 am, we are called on the radio by the lock master saying the fog has thinned enough for us to proceed to lock 8. I grab a life vest and hop off the boat to remove the dock lines and climb back aboard and begin steering up the canal. We pass a tugboat pushing a barge downstream and several private boats as I keep to the side of the canal to give them plenty of room.

As we near the lock, we have to pull over and wait while a down-bound freighter pulls out of the lock. I steer in behind it to line up with the lock and get in his wake and prop wash and in the current of a side channel and I find I can no longer control the boat. I notify the captain and he takes over and gently guides the boat into the lock.

Lock 8 is not very high. It’s only about 1 meter difference here between The canal and Lake Erie. As we travel through the lock and motor up the canal to Lake Erie, I can see where the canal ends at the lake, but nothing further. We motor out into the lake and disappear into a heavy fog. The Captain connects the fog horn which now sounds about every three minutes as we plot our course to WSW 250 degrees at about 6.5 knots. I listen intently for a return fog horn from other boats but none are heard.

As we continue our journey across the lake the fog slowly lifts. We have sandwiches for lunch as we pass long point, the only site of land we see all day. Long Point is a point of land that stretches down from Canada almost to the middle of Lake Erie to catch seamen unaware in the fog. There are many shipwrecks along its point that show how successful it was before better charts, radar and gps were invented.

Before dinner, our cook Geanie cooked herself a birthday cake and we all celebrated her birthday. After this I go back to my cabin for a bath. It has been a long and hot day out on the lake without much wind and it is very hard to find any shade on the boat, so you are exposed to the sun all day. My bath consists of 5 Purell Hand Sanitizing body wipes and a wet washcloth to rinse. I brush my teeth and go to bed.

Wednesday morning I awake about 3 am fully refreshed and report for duty at 4:00am. I went to bed at 9:00 pm so I had a good 6 hours of sleep and that is a lot of sleep on a boat. During my 4 hour shift I rotate from steering, to boat checks – which includes checking all the bilges for water, recording refer temperatures, all the engine, and generator readings in the log book, and bow watch.

Bow watch, when crossing one of the Great Lakes, can be kind of monotonous. There is not much boat traffic out here and you have no site of land. I did happen to see four White Pelicans though. Three flying and one in the water. This is only the second time I’ve seen them on the Great Lakes. We also had some unexpected visitors today. A flock of birds, like swifts, that I assume were chasing bugs as they were flying in and out of our rigging. They stopped to rest and travel along with us for a while but were soon bored and moved on.

We continued crossing Lake Erie when the Captain called a man overboard drill to keep us “on our toes”. After the drill, we leave the rescue boat in the water and bring it around and tie it up along the starboard side. We then all go swimming to cool off in the middle of Lake Erie. It was refreshing while in the water but didn’t last long when we got out to continue our journey.

As we get closer to the other end of the lake, we slow down between Point Pelee and Pelee Island as the Pelee Island Ferry passes in front of us. The first thing that comes into view at the end of the lake is the Monroe Nuclear Power Plant and soon the marker bouys to line us up to enter the Detroit River.

As we get closer to the entrance to the river we begin to see these huge rafts of green lake weeds floating by. We follow the marked channel up the Detroit River and pass under the partly finished Gordy Howe Bridge followed closely by the Ambassador Bridge, And we now have a lot of traffic with freighters and small boats going in all directions in front of us.

The Detroit River has several live web cams and Rob tries to log into one so we can see ourselves pass by. One of the live web cameras is streaming from the historic Bell Isle Dossin Museum (http://www.webcamtaxi.com).

As I’m steering the captain tells me to keep traveling as straight as possible upriver as the M.S. Westcott mail boat pulls up alongside and matches our speed. He hands off some mail to the captain and continues on his route delivering mail to the freighters on the river. It has its own zip code 48222 and provides mail service for the US Postal Service to vessels traveling on the Detroit River. Interestingly, when the Westcott Co. was established in 1874, John Westcott was delivering mail using a rowboat.

After a short while we enter Lake St Clair which is a shallow lake, so we have to follow the marker buoys to stay in the shipping channel. There is a small sailboat race that is using one of the channel markers for their turning point as we pass by. We reach the St. Clair River after dark and finally tie up about midnight in Algonac, Michigan, our final destination.

This was a wonderful, once in a lifetime trip that I enjoyed immensely. The following morning we toured the maritime museum before beginning our trip back to Suttons Bay after being relieved by the next crew change for the final leg of the trip.

At the time this was published, Tall Ships America, a national sail training organization, recently honored our own Captain Ben as “Sail Trainer of the year” for 2023. An honor well deserved.

The St. Lawrence Seaway of North America, by Anne Terry White

A 1,000-Mile Great Lakes Island Adventure, by Loreen Niewenhuis